If you have played any type of video game, you have encountered what we writers call Barks. Yes, in games every character barks, not just the dogs and no, barks are not throwaway lines, maybe we’ll talk about that in another post.

Barks are very unique to game writing. In other media: books, films, plays, everything is scripted. Therefore, you can plan every line a character will say, and nothing is left to someone else. In games though, the player has control of… let’s say a good number of things. Depending on how much your game is linear vs open-world you will need more or less barks, but they are still generally a very common task that writers have to tackle.

So why do we use barks?

They fulfill 2 essential roles:

– Providing players feedback, on their progression, on the dangers in their environment, on the game states….

– Adding flavour to our world: building the fantasy, the lore of the game, creating the vibe and conveying our characters personalities.

Barks are the game talking to you about your performance, about your objectives, or about the world you are in, and doing it with its distinctive voice.

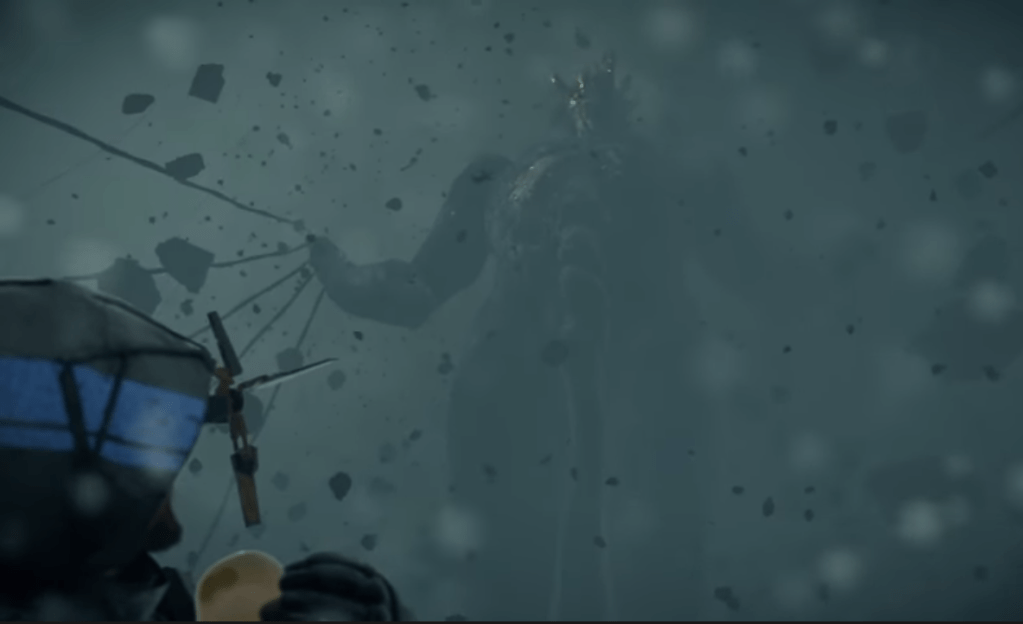

Think Death Stranding, Sam walking alone talking to himself: “Sam, Sam, he’s our man!” or “Here we go again.” These barks embody our main character’s personality, they emphasize his sense of isolation by having him talk to himself. They encourage you to literally carry on and they give you a sense of Sam’s personality and sense of derision. Or think Starcraft and how Protoss barks differ from Zergs: “I feel your presence.” “I hear the call.” “Our duty is eternal.” This is so totally Protoss vs “Metamorphosis completed.” “For the Swarm!” “I will take essence.” Totally Zerg.

In any game that has actions the players may repeat, and / or where writers can’t predict when in the story the player will do them, that’s when we write barks. Think about any shooter game you might have played, you will always need to reload. We want to let players know they are running out of ammo, so we use barks. Barks in that context need to be short and efficient and not distract the players from what they’re doing or become so repetitive that they will annoy you. There are different ways to convey that information and each has a different flavour. They give us an opportunity to distill a little bit of the character’s personality or the world’s fantasy. You could say “I need to reload” or “I’m out of juice” if the weapon is an energy gun or “I’m dry” and they all mean the same thing: the player needs to reload but they taste different.

These days I’m playing Two Point Hospital, and this game has very unique barks that participate a lot in making the game what it is. The game does not have a storyline, but it does not mean that it is not immersive or doesn’t have lore, and that’s achieved through the art style of course, but very much so through the barks as well.

In Two point Hospital, the character giving you feedback on how well you’re doing and on what’s currently happening in that mad place is Tannoy, our PA announcer. Let’s look at a few of my personal favourites:

“Attention! Don’t feed the ghosts, they’re dead. Thank you!”

“Automated food machines need filling manually.”

“We’re sorry about the litter, that you dropped on our floor.”

“There’s a fire. There shouldn’t be a fire.”

“VIP arriving. Please prioritize their amusement over patient well-being.”

Even if you haven’t played the game, reading those lines will give you a sense of the game mood. It’s humoristic and it’s not a realistic simulation game. You can expect crazy illnesses and funny looking patients. Each of the lines above serves 2 purposes, the tone like we discussed and player feedback.

The first bark lets you know that you have ghosts roaming around the hospital. If you had not seen this because you were busy building and furnishing new rooms at the other side of your estate, you might want to have a look and possibly assign a janitor to take care of it before the ghost drags your patients screaming outside.

The second one is a warning that some of your automated machines are empty and need restocking, but again the way it’s written (and the way it’s voiced) contributes to the tone and the game consistency. I could go on like that with each of them. Barks are real writing, don’t ever turn down an opportunity to work on that!

In Two Point Hospital, they are like the binding agent of the whole game experience, because they are voiced and the rest of the text is written, meaning it’s a lot less certain that the player will ever bother reading it. If you manage to express the game’s personality through the barks, you may very well light the spark that will make the players want to read more about what’s written in the game.

Of course Two Point Hospital’s writers have done the job perfectly and you will not be disappointed if you pay attention to every single piece of text that populates the UI. Barks are just one element of lore, the one that is the most accessible to the players, but every other piece of text is written with that same sarcastic zing. Characters’ descriptions in the hiring UI will tell you that this doctor “Will work for peanuts” or that this assistant “Thinks their life is a romcom” or that this nurse is “Hangry”.

Depending on the game you’re making, barks may well be what the players will hear and remember the most from their experience, because they are tied to actions that they will repeat over and over. They may seem like an detail, but Two Point Hospital shows how they can capture the atmosphere of your game and contribute to making it more fun for the players. Of course, humour applies in their context and their barks can be longer because the gameplay can tolerate that, while it would be much more complicated in an action or stealth game. Still their barks focus on doing these 2 things and they do it very well: Feedback + Flavour.

Barks will often stretch our creativity because we think there are only so many ways to say “reload” or “enemy there”, but if you think about it in conjunction with delivering game vibe and fantasy, you’ll see that it’s not just what you’re saying, it’s how you say it! A handy skill to have, both in game development and life.